Major spoilers ahead for Phantom Thread. If you haven’t seen it, it’s currently streaming on Netflix and well worth your time!

If you search for Phantom Thread on Netflix, you’ll see it’s categorized as a romance, which is at once completely true and completely eyebrow-raising. I doubt Paul Thomas Anderson is capable of creating a straightforward romance, and true to form, the film’s central relationship between Alma and Reynolds is built entirely around their distance, not their closeness, making this the most unromantic romance you can imagine.

Phantom Thread is exactly the kind of insular film I enjoy so much, but it’s an awkward setting for the genre. Much of the film takes place in the same house, which serves as Reynolds Woodcock’s home and workplace. It’s easy to forget that a world exists outside those walls when seamstresses simply appear in the morning, and clients manifest in a cloud of luxury on the threshold of the door. The House of Woodcock is a closed ecosystem, where Reynolds plays tyrant and Cyril plays both policeman and politician. The absurdity of this is never lost on the film, and Alma is the deliberate vehicle of contrast. The scrape of her toast, the gunshot of her kettle— these moments connect the House of Woodcock reluctantly to the existence of things other than Reynolds’ sanitized preferences.

Alma’s and Reynolds’ romance is built from the discomfort of friction, and the intensity ratchets up until Alma explodes during the world’s most awkward dinner date.

Alma: All your rules, and your walls, and your doors, and your people, and your money, and all this - clothes! - and everything, this, this, this game! Everything here! Nothing is normal, or natural— everything is a game.

Reynolds: If it’s my life that you’re describing, it’s entirely up to you whether to share it or not.

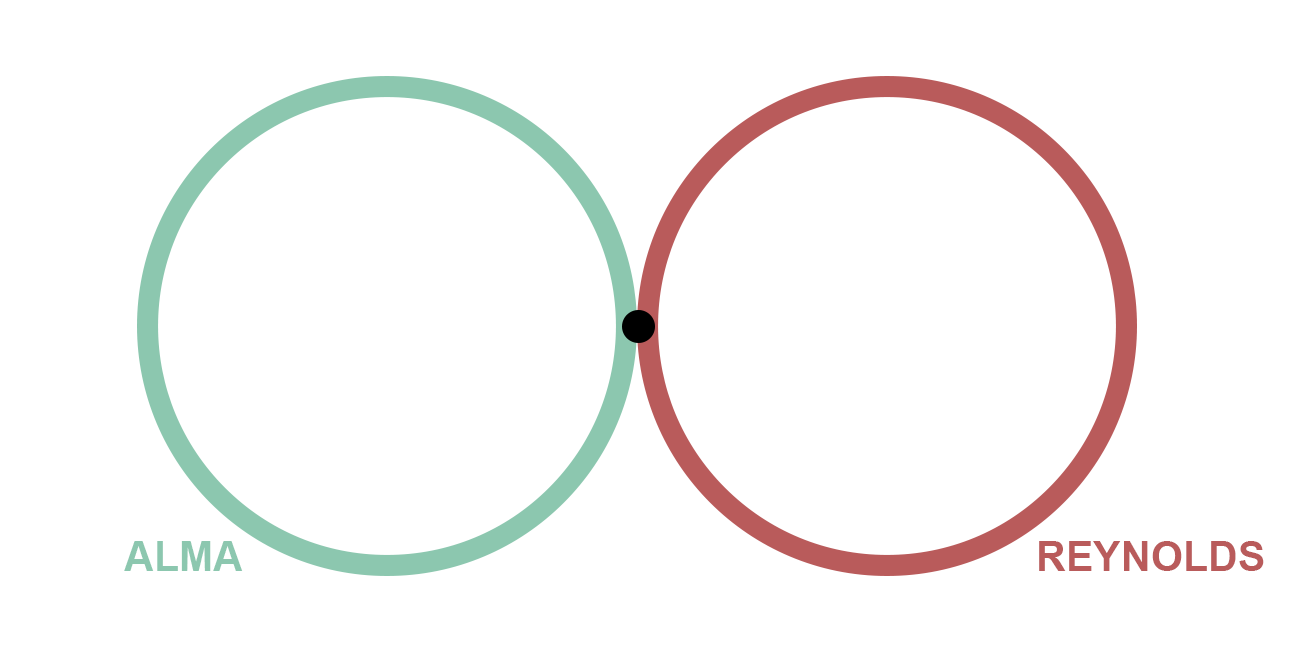

As Alma well knows, the choice to “share Reynolds’ life” is not really a choice at all. What is there to share? Alma can partake in the trappings as much as she wants, but she knows she’s not sharing in Reynolds’ life, not really— and meanwhile, Reynolds cannot distinguish his life from its trappings, and therefore cannot understand Alma’s dissatisfaction. The Venn diagram of Alma and Reynolds probably looks like this,

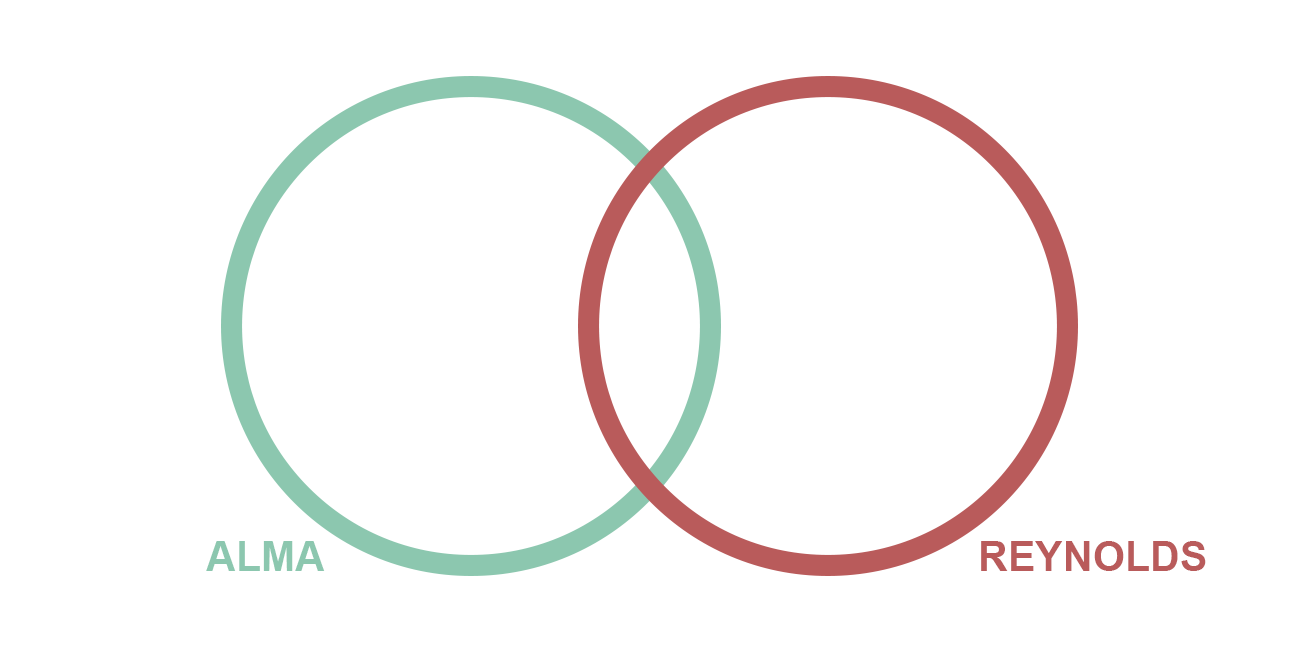

or maybe more accurately like this,

meaning for all that these two people live in the same house, breathe the same air, and “share their lives”, they experience almost no real overlap and are adjacent only as dictated by Reynolds and his peculiarities. And yet, the point of connection is powerful enough that it holds Alma and Reynolds together, even as they seem to strain to be apart— the joy of this film is taping two repelling magnets together and seeing whether attraction or repulsion will win out.

And even then, the repulsion between Alma and Reynolds is never as simple as disliking the other person despite loving them. Instead, it’s their resistance to becoming something other than what they already are, especially in Reynolds’ case. It is a painful process to go from being one person to two, and to invite your insular circle to overlap with someone else’s is to cede your borders and acknowledge change even as you clutch at control. Reynolds’ circle has consisted solely of his sister and the ghost of his mother for many years. For Alma to lay siege would therefore be to expect an impossible victory, but she does it anyway.

It’s ironic that some of the best evidence that Alma’s siege is working is one of the film’s crueler scenes, with Reynolds calling Alma a “terrible mistake” while unaware that she has quietly entered the room behind him. Alma and Cyril then talk business with extraordinary calm, putting Reynolds to the side like an overexcited toddler. This prompts Reynolds to say:

What a model of politeness you two are! There is an air of quiet death in this house, and I do not like the way it smells

These lines are a revelation, because they’re a direct reversal of Alma’s and Reynolds’ early dinner date. Now, it is Cyril and Alma who play the game to perfection, and it is Reynolds floundering in the wake of their artifice, unable to fathom how they could be so unnatural. His proclamation that “there is an air of quiet death in this house” is the richest irony— if there is an air of death, it is the exact atmosphere he worked so hard to perfect. If Alma and Cyril breathe that air, it’s at the subjugation of their lives to Reynolds’ wishes. And if there’s a smell, it’s only the rotten stench of Reynolds’ own stagnation. Quiet death has always been the foundation of the House of Woodcock; that Reynolds is now aware of it is proof that Alma has cracked his fortress and changed him, even if he resisted that change every step of the way.

I think there’s a significantly worse version of this film where a scene like this implies that if Reynolds could only match Alma’s love, then the two of them would be level at last, seeing eye-to-eye as partners. It’s a foolish wish, and the movie rebuts it admirably in the New Year’s Eve sequence, which is one of its best. For once, it is Alma who refuses Reynolds’ preferences, and after realizing that Reynolds will not accompany her, she simply goes to her party solo. And shockingly, later, Reynolds - alone and unhappy on New Year’s Eve - puts on his coat and goes out to find her, tears in his eyes as he searches the partying throng for his wife.

If you’re anything like me, watching this sequence made naive hope flare high. Now, with Reynolds willing to make a concession, the two would spot each other across the crowded room, clock striking the new year, and come together as they never have before. Instead, this scene ends in complete anticlimax. Reynolds finds Alma, but far from rejoicing at their togetherness, they stand as though a million miles away, lonelier together than they would have been apart.

This is the deep unhappiness of compromise. Reynolds is incredulous that he decided to go to the party at all (admiring his own gallantry, as it were), never mind that it’s clear he would’ve rather been dragged over hot coals. Alma can’t appreciate the modicum of effort Reynolds has made, because she resents that she had to apply such force to see such reluctant results in the first place. This scene is the film’s confirmation that there is no such thing as compromise for these lovers. Try as they might to make their Venn diagram look like this,

it inevitably looks like this

or like this, as in the NYE scene.

This is the critical foundation that allows us the climax of the film. The New Year’s Eve sequence makes the necessity of the omelette clear. It’s the last choice left to Alma and Reynolds, the only choice, or at least the only choice that allows them to be together. After an entire movie of the wrong Venn diagram - the wrong relationship - Alma and Reynolds finally decide to create this one instead, no matter the cost.

This is why, in the final sequences of the film, the House of Woodcock falls away like so much paper in the wind, and the trappings of the old world disintegrate in favor of the new one that Alma and Reynolds have created for themselves, together. And however bizarre this new world is, it’s something they commit to sharing, in a true sense of the word.

What amazes me about the omelette sequence - besides the cooking close-ups, the writing, the music, and every single other detail - is that after the shock of what’s happening subsides, what I’m left with is the strangest little curl of envy. What Alma and Reynolds have is so fucked up (no other way to describe it), but the simplicity of the solution to their problems evokes an uncomfortable jealousy. Who wouldn’t wish for a physical cure to an emotional disease? As strange as Phantom Thread is, its central conflict is completely relatable— the unknowable distance between people is the endemic problem of any relationship. This makes the omelette a tempting prospect, even beyond the butter and chives, because it marks a straightforward path for Alma and Reynolds to be together.

Of course, no path that contains voluntary poisoning is truly straightforward, and the cure is not the omelette itself, but the commitment it symbolizes. Unable to cure the distance between them by recommended means, and unable to walk away from each other and obviate the need for a cure at all, Alma and Reynolds cure themselves by choosing another disease entirely. The difference is that this disease is one they’re willing to live with: that the price of being together is the cost of everything else, including their own selves. To make this particular omelette, Alma and Reynolds simply have to crack their hearts wide open, and they’re served up with such relish, such intensity, and such undeniable beauty, that it leaves me a hungry, hungry boy.

Culture Crumbs

This hunter harris newsletter on Phantom Thread, which offers an incredible breakdown of the NYE scene

One of the weirder recent film happenings: a Chinese streaming site changed the ending of Fight Club to be a little more authority-friendly, then restored the original film after widespread mockery

This year’s Oscar nominations will be announced on Tuesday morning. Will bloopers be doing Oscars coverage? The answer is yes, because we all need to do our part to #GetAlanaHaimHerOscar

And while I’m on my PTA/Licorice Pizza soapbox, shout out to this article, which tells me what I need to know: How to Dress like Alana Haim in Licorice Pizza

This real ad that I got from Facebook. Can someone please tell me what this says about me???

Thanks for reading! Please consider subscribing if you haven’t already— it’s free!

Venn Diagrams and film criticism! It's the marriage I never knew I needed.