Spoilers for The Big Short ahead

Hollywood, it turns out, loves economics. I don’t just mean that Hollywood likes making money, although that’s certainly true. I mean that Hollywood loves depicting money, especially Wall Street money and all the intensity that accompanies it. In the past decade, shows like Billions and movies like The Wolf of Wall Street have cemented the financial sector as the perfect high stakes and high drama story premise. No surprise, then, that the 2008 financial crisis - the largest in recent memory - inspired an iconic financial film: The Big Short.

Adam McKay’s The Big Short follows the few people who saw the crisis coming before anybody else and acted by shorting, or betting against, the housing market. The film made a huge splash and gained a reputation for actually caring about the economics behind the drama, so in today’s newsletter, I want to revisit The Big Short in-depth and examine its unique storytelling approach.

--

One of the key aspects of The Big Short’s narrative, which sets it apart from other financial films like Margin Call, is that The Big Short’s protagonists are all industry outsiders. They may be financial veterans, but these characters’ conviction that a financial apocalypse is on the horizon automatically positions them as contrarians— salmon swimming against the stream. Because we begin the film in 2005, The Big Short isn’t a film about reaction; it’s a film about prediction. And because we, the audience, have the benefit of hindsight, The Big Short becomes a Cassandra tale, where we watch our Wall Street prophets divine the future, then fail to convince anyone else of it.

This dramatic irony means that while the characters need to be convinced of the incoming crisis, we don’t. Scenes where characters learn about a potential collapse are quick, dramatic, and undeniable. In one of the movie’s pivotal moments, Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) explains the impending housing market collapse to Mark Baum (Steve Carell) and his associates using a stack of Jenga blocks. Jared warns of financial armageddon, but an associate pushes back: “You’re completely sure of the math?”. Vennett scoffs in response and speedily assures him the math is airtight.

This scene is played for comedy and drama, but its other implication is that the financial crisis could have been predicted by equations and models, so long as you didn’t make any mathematical errors. However, when making economic predictions, the question shouldn’t be “Is your math correct?” but rather “Is the data you’re using to do the math the right data for the question you’re trying to answer?”. In his pitch, Vennett cites an explosion of sub-prime mortgages (riskier housing loans that might not get paid back) as evidence for a housing bubble. And, because you and the film both know the crisis happened, that evidence is framed as incontrovertible: the Jenga tower comes tumbling down.

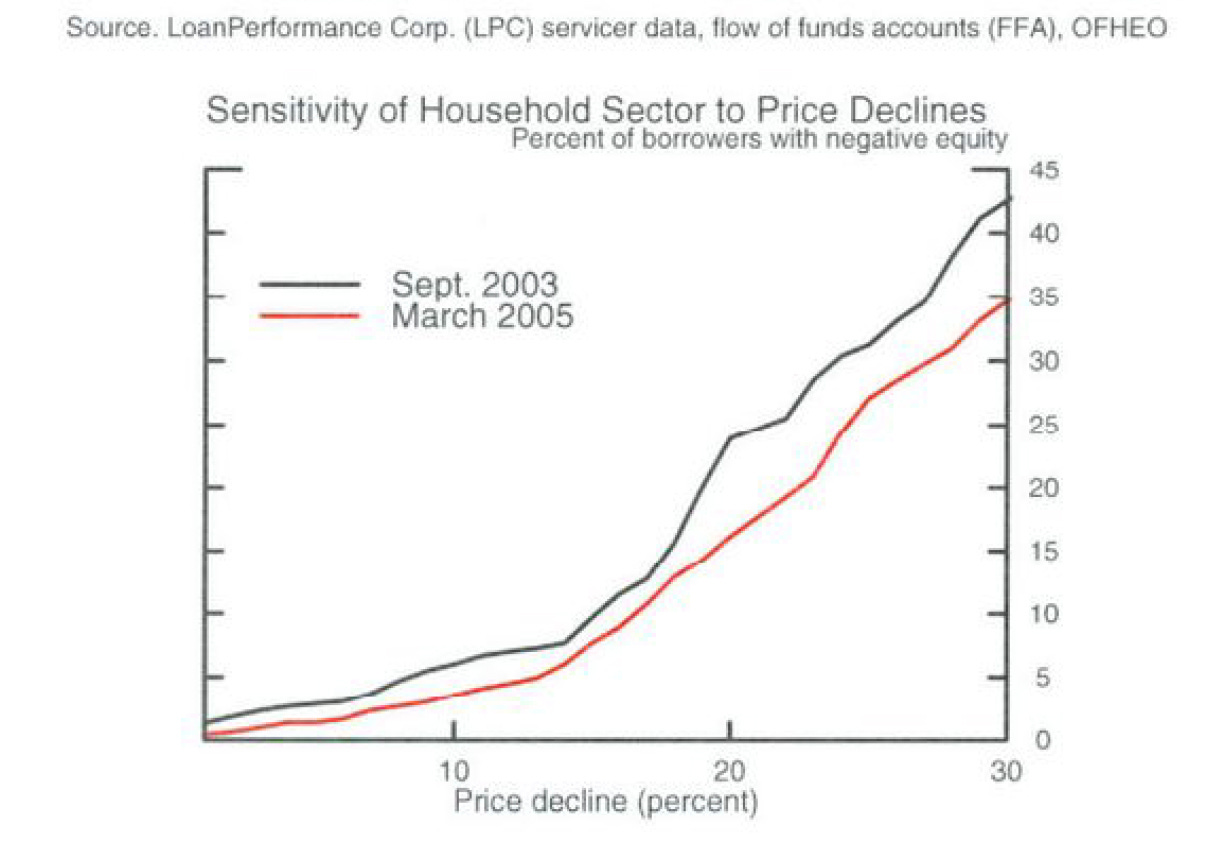

The Big Short doesn’t feel the need to question the data it presents, but pre-crisis, there were a lot of questions. The data below, for instance, shows that the housing market actually became less vulnerable to price declines from 2003 to 2005, even though we now know that it was becoming increasingly unstable over that period. This is a small slice of the 2005 evidence that could convincingly suggest we had nothing to worry about.

I don’t bring this up as a “gotcha!” to The Big Short, because I don’t believe the film should inundate audiences with data. What I do believe, however, is that by failing to acknowledge the ambiguity that existed pre-crisis, The Big Short does us a disfavor. Presenting the financial crisis as a certainty is not mere narrative convenience; it allows the audience a knowledge high-ground that’s informed entirely by hindsight. The Big Short encourages us to see 2005 through a post-2008 lens. Therefore, instead of asking why a few people were able to predict the market’s collapse when no one else was, we ask why no one else will believe their warnings.

It’s a fair question to ask, but it shifts The Big Short’s focus. This isn’t the story of a few underdogs who managed to piece together a difficult puzzle. It’s the story of a system burying its head in the sand in the face of certain crisis. The Big Short cements this in the movie’s final scene. After months of trying to understand how this happened, Mark Baum realizes that no one acted on his warning, because “They knew. They knew the taxpayers would bail them out. They weren’t being stupid, they just didn’t care.” The Big Short posits that the banks who refused to believe the market would collapse were not idiotic but rather profit-hungry monsters who knowingly took on risk at the expense of the American people. The central tenet of the film isn’t economic— it’s moral.

I’m not criticizing the fact that The Big Short is a deeply didactic film. The financial crisis revealed real problems - broken regulation, self-interested actors, problematic incentives - and therefore had legitimate moral implications. The Big Short’s demand for accountability is a justifiable one. What should be critiqued, however, is the film’s one-dimensional morality. By saying “They knew”, The Big Short does not simply make the bank villains— it makes them knowing, active villains. This is reductive for two reasons.

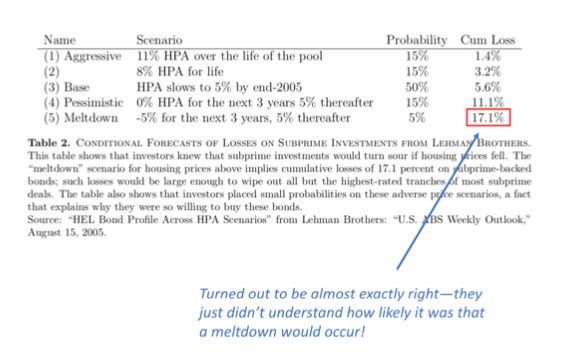

First, it’s questionably true. If the banks knew the housing market would collapse and didn’t care, they were taking on a lot of risk counter to their own interests. Yes, some banks received government bailouts, but Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers disappeared. This table from Lehman’s 2005 outlook shows that Lehman knew the potential consequences of a housing market decline but underestimated the probability. If they truly understood the fire they were playing with, they’d probably still be around.

Second, and more importantly, presenting the banks as actively immoral villains who knew exactly what havoc they were wreaking ignores a far more critical cause of the crisis: complacency. Complacency implies an unfounded optimism, and the 2008 financial crisis was full of that. For 30 years, Americans had seen reduced economic volatility in a period called “The Great Moderation”. And for more than 30 years, homeownership was a foundation of the American dream and a bipartisan goal in D.C. People wanted homes, politicians wanted constituents to have homes, buying homes required the financial sector, and the financial sector responded to that demand.

The problem with this chain of events is not that banks pushed complicated mortgages upon those who shouldn’t have them (those “exotic” mortgages already existed in the eighties). The problem was that after decades of economic prosperity, people believed the housing market would never decline. People believed that a good short-term ensured a good long-term. People, and more specifically the banks, therefore fundamentally misunderstood the risk they were taking on through housing investments.

Being complacent isn’t absolution. It’s possible to be complacent to the point of immorality, as was likely the case in the financial crisis. However, while they may be related, complacency and immorality are not the same, and it’s an important distinction, especially in a movie as didactic as The Big Short. Immorality is easy to distance ourselves from. When characters make truly immoral decisions on screen, they become monsters, separate from ourselves. We think, “If I were in that situation, I would never make that choice”. Complacency, on the other hand, is far more insidious, because it’s recognizable as human nature. Complacency is inertia, comfort, and optimism all rolled into one, and it’s hard not to see that instinct within ourselves.

A movie like The Big Short wants you to understand how the financial crisis happened and, more importantly, how it could happen again. Its final text card highlights that since 2015, large banks have been selling billions of “bespoke tranche opportunities”, a similar product to the ones that played a large role in the crisis. The message The Big Short leaves us with is that nothing has changed, and the cycle of immorality will repeat. It’s a worthwhile warning, and one that prompts us to be cynical.

But in a way, it also suggests a simpler world, because if the crisis were caused by active immorality, regulation and increased accountability could prevent something like this from ever happening again. The truth is that there has been regulation and increased accountability - Dodd-Frank, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau - but that’s no guarantee of safety. The scarier truth that The Big Short glides over is that complacency is harder to recognize, harder to predict, and harder to regulate than corruption, but if we want to understand how the Great Recession could happen again, it’s the force we need to understand most.

Citations: For a purely economic perspective on how complacency, false expectation, and a bubble mentality caused the financial crisis, check out this fantastic paper by Foote, Gerardi, and Willen (2012), which is very accessible and provides much of the evidence in this essay. Further credit to Karen Dynan, whose course on The Great Recession inspired and contributed to this piece and to Greg Ip, whose WSJ review of The Big Short touches on similar concepts.

Culture Crumbs

The trailer for Venom 2: Let There be Carnage, one of my most anticipated films of 2021. To the haters:

Olivia Rodrigo’s new album, Sour, which is not a movie but is such an evocative break-up narrative that it might as well be

James Acaster’s new stand-up special Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999, recommended by my sister and worth every minute of its two-hour runtime

News that The Phantom of the Opera is getting remade as a thriller with Scooter Braun producing. Hard pass.

Me, trying to show my roommate the genuinely good 70s outfits in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre by googling “texas chain saw massacre outfit” and getting these horrifying results instead

That’s it for this week! Thank you for reading, and welcome to all the newcomers. I’ll be taking a break from bloopers and breadcrumbs during June to shift my focus from writing to watching, but I’ll be back soon enough!

Michelle! What wonderful analysis. The writer of the book on which the movie is based, interestingly, has made a career on writing these reflective books looking back on events where someone knew (or should have known) something different. You probably know he wrote "Moneyball," and his newest work "The Premonition" is on the pandemic.

Anyway, you should watch one of my favorite documentaries on this subject too, "Inside Job." It's great!